The Kaneko Ginkgos of Lancaster County

Massive, towering ginkgo trees (Ginkgo biloba) are scattered throughout Lancaster Cemetery. The intriguing story of how they came to be there centers upon a brilliant yet humble young man from Japan who spent the last eight years of his life in Lancaster 125 years ago. The story of these trees and of that man, though told in part before [4,11,15], is chronicled more completely here. And while some details of the narrative remain uncertain, the broad strokes of the story stand remarkable and true.

Planted in 1896 as perhaps 5-year-old saplings, the Kaneko Ginkgos are 130 years old today. In “ginkgo years,” though, they are still children for this prehistoric species can live more than 1000 years, perhaps as much as 2,500. This means that these trees are not only a priceless part of Lancaster County’s past and present but, deo volente, a permanent part of its future as well — a living part potentially more enduring than even our historical buildings can hope to be.

The future of the Kaneko Ginkgos, however, is not assured. Large trees require upkeep that can be punishingly expensive for cemeteries that are neither profit-making nor, in most cases, beneficiaries of widespread public support. Only a few years ago a storm triggered the need for $30,000 in tree-related care at Lancaster Cemetery, an unbudgeted amount that was a significant struggle to raise. Hopefully, with more Lancastrians aware of both the ginkgos and the exceptional man they memorialize, concern and stewardship of these treasures will grow and continue for many years to come.

George Kinzo Kaneko

George Kinzo Kaneko was born October 10, 1865 in Hanamaki, a city in the Iwate Prefecture on the north end of Japan’s main Honshu Island. He was the fifth of seven brothers in a well-to-do family that belonged to Japan’s Samurai class [15]. Kaneko was, in fact, “the son of a samurai” [18] .

In 1884 Kaneko came to America to study English in preparation for entering the diplomatic corps [11; see Note 1]. At the suggestion of a Japanese student at Franklin and Marshall College named Kamenaka (sometimes spelled Yamamaka) who was then in his senior year, George was sent by the Japanese Consul in New York to Franklin & Marshall Academy.

Franklin and Marshall Academy was a private preparatory school owned and operated by F&M College until its closing in 1943. Kaneko spent three years at the Academy, which sought to prepare boys through Grade 12 for college. It was during his Academy years that Kaneko began to receive instruction in the English Bible through catechetical lessons under Prof. E.V. Gerhart, D.D. [15] Kaneko then entered the freshman class of the College in September 1887.

When Kaneko graduated from F&M along with 26 other seniors in 1891, he earned the honor of class valedictorian [18]….a remarkable feat given that English was his second language. As a student Kaneko “was thoroughly conscientious and occupied positions in his various classes that clearly marked his scholarship.” [15]. He was also “very popular among the students at the college” [5], and was “universally respected and formed many close friendships.” [15] While at F&M, Kaneko was converted to Christianity by W. E. Hoy, himself later a distinguished missionary to China. Kaneko then decided to study for the ministry, and after graduating from F&M immediately entered the Reformed Theological Seminary (now Lancaster Theological Seminary). [11]

Kaneko’s conversion to Christianity happened very quickly. A newspaper article from 1885 describes the journey of faith followed by Kaneko and another Japanese student:

Outside of their daily studies they have received Christian instruction twice a week from Mr. W.E Hoy, a member of the senior class in the theological seminary. (See Note 2) The interest these boys showed in this particular direction was marked right along and was encouraging to their teacher, but the fruition of his labors was still more manifested when some time ago, without even being asked, both in their gentle and unassuming manner, asked their teacher whether they could not be baptized and taken up as members of the Christian church. On Good Friday (April 3, 1885) in the college chapel during preparatory services for the Easter communion, having already a few days ago passed a very credible examination before the consistory, both George Kinzo Kaneko and William Kenjiro Sato were baptized and taken up as members of the Reformed Church. [10]

During his time at the Reformed Theological Seminary, Kaneko was a guest speaker at religious services in Lancaster County and beyond [16]. He graduated from the Seminary May 14, 1894 and was then licensed to preach the Gospel to Lancaster Classis at its annual meeting in New Holland PA. [15] In order to further advance himself in Hebrew and Bible studies, he remained for a year of post-graduate study with Rev. Frederick A. Gast, D.D., Professor of Hebrew and Old Testament Theology. At the same time he also taught Japanese at F&M and occasionally gave guest lectures and sermons to local congregations and other groups, many of whom had never seen a Japanese person before [2, 5, 7].

Towards the end of that academic year, right after he had finished a post-graduate course in Hebrew [7], Kaneko obtained a Professorship of Old Testament Literature at Tohoku Gakuin College in Sendai, Japan, and was to have sailed for his native home the latter part of May 1895. [5] He had already shipped his books home and was mere weeks away from debarking for Japan when his health, which had been declining for several months from pulmonary issues (due to tuberculosis), failed rapidly [7, 15]. He entered St. Joseph’s Hospital on April 21,1895, and died abruptly a few minutes before noon on Wednesday, May 15, 1895 [5, 8]. Funeral services were held at 3:00 pm on Friday May 17 in the Theological Seminary’s Santee Chapel [5], and interment was made on the F&M lot in Lancaster Cemetery. [15] George Kinzo Kaneko was only 28 years old when he died.

In reporting his death, The Lancaster Examiner said that Kaneko was “brilliant” and “of a gentle and amiable disposition, and had won the honor and respect of all with whom he came in contact.” [8] Kaneko’s demise, it continued, “will be lamented by the faculties of both the college and seminary, the student body of these institutions, and his many acquaintances and friends.” The Lancaster Intelligencer opined that “by way of gentlemanly conduct and Christian deportment, Mr. Kaneko was worthy to be copied.” The Lancaster Inquirer, meanwhile, noted that by 1895 a number of Japanese had attended either Franklin and Marshall College or the Reformed Seminary, but “Kaneko was the brightest of all.” [6] Finally, in an obituary written for F&M, Rev. Ambrose M. Schmidt said that George Kaneko “was the very soul of honor, the perfection of politeness, and generous to a fault.” [15]

When one considers these descriptions of his character, personality and demeanor, and the sort of student and person he was, George Kinzo Kaneko seems to have achieved many of the ideals to which Japanese samurai aspired. As described by Inazo Nitobe [13], the Samurai code of behavior included not only Courage and Justice, but also: (1) Benevolence and Generosity, (2) Politeness, (3) Honesty and Sincerity, (4) Honor, (5) Loyalty, and (6) Character and Self-Control.

The Ginkgo Trees

Immediately following Kaneko’s passing, memorial gestures were made both here and in Japan. The Reformed Church’s Classis of Philadelphia raised funds for the Kaneko Memorial Building in that city [1], and in Sendai the Kaneko Memorial Press began publishing religious literature and church-related reports. Memorial gestures also flowed across the Pacific in both directions. F&M, the Seminary, and others [e.g., 17] promptly raised a memorial fund that helped to secure larger buildings and more grounds for Tohoku Gakuin at Sendai. [Note 3] In short order, the fund delivered $25,000 to that college and training school. [15] This extremely generous gift was the equivalent of $770,000 in today’s dollars.

At about the same time (1896), multiple maidenhair or ginkgo trees were sent from Japan to Lancaster to honor Kaneko’s memory and to express gratitude to F&M for permitting his burial within the college’s cemetery plot. The exact number of trees is in question, however. A 1959 article in the Lancaster Sunday News cited four trees, three females and one male, with two going to F&M (planted at opposite ends of the old Academy Building) and two to Lancaster Cemetery. Yet Jerry Smoker, who was associated with the cemetery for more than 35 years as trustee and director, and whose mother volunteered at the cemetery as well, has stated that six ginkgos arrived from Japan, three females going to F&M and three males to Lancaster Cemetery [4]. [See also Note 4]

Exactly who in Japan sent the trees is in question as well. The 1959 article said the trees were sent by Kaneko’s parents but this cannot be true; both mother and father died before George did (1880 and 1882 respectively). [9] Smoker believes the government of Japan sent the trees [4] and this is at least plausible because of Kaneko’s samurai heritage. Being the recipient of a gift from a foreign government would be extremely noteworthy for Lancaster County. On the other hand, Satoshi Hino of Japan’s Tohoku Gakuin University has speculated that perhaps Mr. Kaneko’s brothers sent the trees. [9].

In any event, we can be sure that however many trees there were and regardless of who sent them, half were planted at Lancaster Cemetery and half at F&M. It is further true that the trees at F&M caused problems. In particular, one or more of the trees turned out to be female and, after perhaps 15-20 years, began producing prodigious amounts of fruit. Ginkgo fruit typically carpets the ground for 4-6 weeks in Autumn, and as it decays becomes dangerously slippery and repugnantly smelly (the odor has been variously described as similar to rancid butter and rotting milk; vomit and dog excrement; limburger cheese; and dirty gym socks). With the trees standing next to a building that served as both dorm and dining hall, the fruit irritated campus residents who accordingly urged the ginkgos’ removal. Finally in the Spring of 1959, F&M’s Campus Improvement Committee agreed and the trees were to be cut down the following summer.

Plans to destroy the ginkgos, however, did not sit well with Elizabeth Clarke Kieffer (1899-1991). Kieffer — a locally prominent author, genealogist and librarian at both F&M and the Lancaster County Historical Society — was a force to be reckoned with, and tree lovers led by Kieffer were reportedly “up in arms” over the issue. Extensive newspaper coverage, no doubt instigated by Kieffer, summarized her views:

While ginkgos may become stinkos for a few weeks of the year, their beauty the rest of the time should redeem them from the woodsman. And the real historic interest of the trees, apparently unknown to the improvement committee when it handed down its verdict, is the clincher which should save the towering ginkgos. [11]

In response to such local objections, and perhaps also fearing an international incident, F&M decided that the ginkgos should be relocated to Lancaster Cemetery [4]. This would have entailed considerable expense and effort since the trees were of some size by 1959. But even large trees can be successfully moved and this is what reportedly was done [4]. This turns out to have been a happy solution all the way around: The trees themselves are thriving in their current residence. And unlike the campus Fummers of the ’50s, not a single permanent resident of Lancaster Cemetery has ever complained about maidenhair fruit. In fact, the fruit draws local Asian families to the cemetery each fall to collect ginkgo nuts, which are a valued commodity in Japan, Korea and China. And finally, Lancaster County has a priceless piece of living botanical history preserved in whole rather than halved 60 years ago.

Unfortunately, which specific trees are the Kaneko Ginkgos is somewhat uncertain today. Eight ginkgos live in Lancaster Cemetery and they show considerable variability in their trunk circumference (trunk size being an imperfect indication of age). One female is obviously younger than the rest and cannot be a Kaneko but could well be a genuine offspring. The Pennsylvania Co-Champion Ginkgo (a male; top photo), along with another tree approaching similar size, are almost definitely Kaneko Ginkgos. However, at present it’s difficult to draw conclusions about the remaining five trees. [See Note 5.]

The issue is all the more difficult without knowing for sure whether the Kanekos are four or six in number. An answer to this latter question is unknown in Japan [9] but perhaps may eventually be discovered somewhere in records at F&M. Of the two possibilities — four trees or six — one might be inclined to favor the 1959 newspaper article which cited four trees. The article after all was written closer in time to the actual events. Further, Elizabeth Kieffer, a major source for the article, was not only a one-time employee of F&M but also by profession a trained purveyor of historical facts. It’s difficult to imagine this woman being wrong about this basic piece of information.

On the other hand, the newspaper article did contain some major errors —i.e., that Kaneko’s already-dead parents had sent the trees; and the consistent misspelling of Kaneko’s name. Also, Jerry Smoker, who supposes six trees, has been associated with Lancaster Cemetery for almost four decades, an impressive credential in itself. And the fact remains that seven very large ginkgos do indeed live in the cemetery, so the possibility of six being Kanekos is perfectly plausible. The matter thus remains unsettled.

Why George?

Kaneko’s tombstone, references to him in F&M documents, and his obituary all use the name George Kinzo Kaneko. This moniker was not his “given name, middle name and surname” because Japanese do not have middle names. [12] Rather, Kinzo was his Japanese name and George was adopted when he came to America.

It’s not uncommon for Asian immigrants and exchange students to pick English first names. In the case of Chinese, this practice is partly because their language contains sounds that don’t exist in the West and Americans thus have difficulty both pronouncing and remembering many Chinese names. As a personal preference or perhaps under implicit pressure, then, some Asians pick English names for convenience of communication. This reason doesn’t apply to the Japanese, however, because all Japanese characters are an easily pronounced consonant-and-vowel, and so English speakers usually have no difficulty pronouncing their names.

Still, as the amiable and gracious person that he was, Kaneko would have agreed to any suggestion that he pick an English name in order to better assimilate and to make others more comfortable. But why George in particular? There are two reasons.

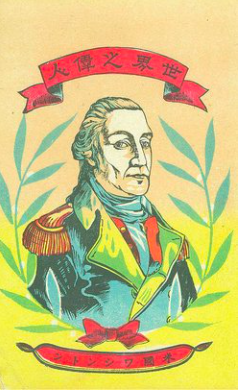

First, many Japanese in Kaneko’s day felt admiration towards our founding father, George Washington. As noted by Tim Asamen,

The story of a boy who chopped down a cherry tree and couldn’t tell a lie, and then grew to become commander of the Continental Army and president of a new nation, was an excellent example of shushin (moral education), and it had been incorporated into elementary school readers in Japan during the Meiji period (1868-1912). [3]

A second and more pedestrian reason for picking George was that the name was phonetically similar to a common Japanese name for boys, “Joji.” [3]

For these two reasons then, George was perhaps the most common English name adopted by persons of Japanese heritage, and it’s not surprising that Kinzo selected it. (See Note 6)

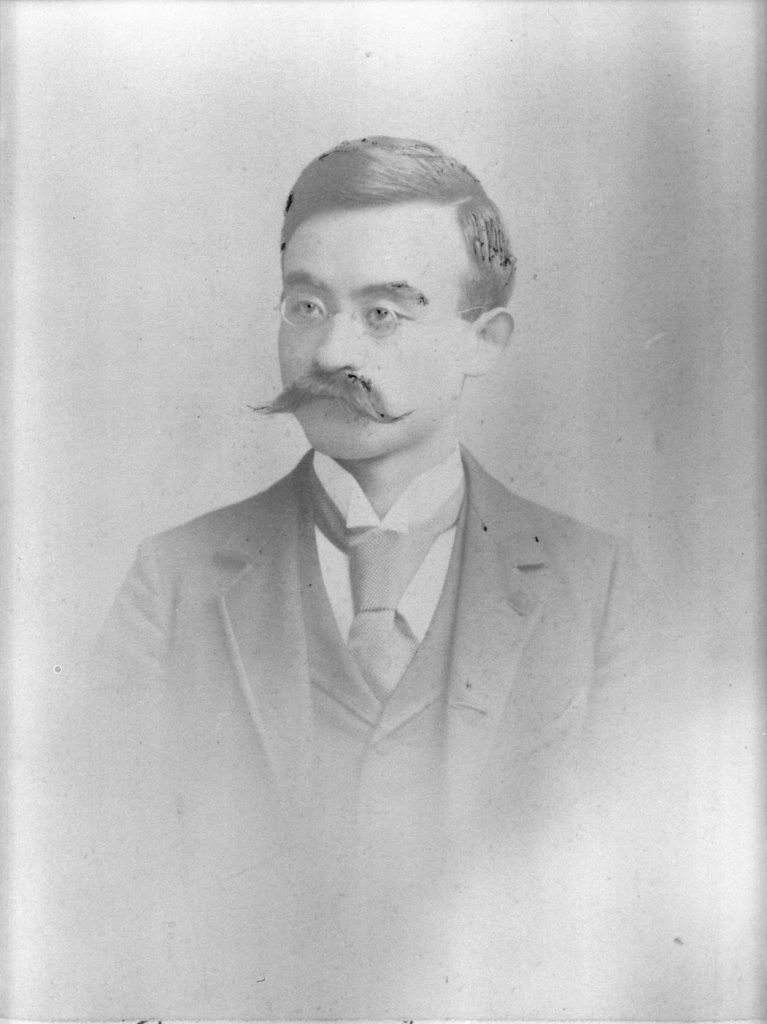

Photos

Until March of 2020, no one in Lancaster County knew what George Kinzo Kaneko looked like. He was simply a name on a tombstone or someone mentioned in old newspaper articles. But years ago, George’s relatives sent four photographs to Tohoku Gakuin University, and TGU’s Satoshi Hino has been kind enough to relay those photos to the present author [9] . In Mr. Hino’s words: “Some of the photos were given by one of Kaneko’s descendants, who still lives in his hometown in Hanamaki of Iwate Prefecture, about 35 years ago when I had been a staff member of the Centennial Office of our school, Tohoku Gakuin (North Japan College).”

The photos shown below include George: (1) with his grandmother and father; (2) with two brothers and father; (3) as an F&M student; and (4) as a seminary student.

Additional photos show (5) George Kaneko’s modest tombstone; (6) Elizabeth Kieffer, photo courtesy of LancasterHistory; (7-8) the old Academy Building adjacent to which two ginkgos reportedly lived, and also Harbaugh Hall where George probably resided (photos credit of Franklin and Marshall College); (9) Santee Chapel where his funeral was held, as it looks today; and (10) a vintage Japanese postcard of George Washington from the Meiji period. The upper banner reads “Great Personages of the World”, and below it, “America’s Washington” (photo credit of Tim Asamen, 2016). Also, (11-12) ginkgos in Lancaster Cemetery.

Notes

- The Samurai had been abolished as a feudal fighting force in the 1870s, after which they moved into professional and entreprenurial roles. Although they were only 5% of the Japanese population, Samurai often became foreign exchange students because they were ambitious, literate and well-educated. [14]

- F&M’s Harbaugh Hall, where Kaneko probably resided, housed both F&M and Lancaster Theological Seminary students at the time.

- Tohoku Gakuin University began in 1886 as a boys’ school and is now the largest private university in northern Japan. TGU has had a special relationship with both Lancaster Theological Seminary and F&M College from TGU’s beginning. [15,18]

- Complicating the matter even further, some F&M faculty believe that “Kaneko’s family sent two ginkgo trees. One was planted in front of Old Main, the other in Lancaster Cemetery where Kaneko was interred in the college’s plot.” (Personal Communication from Prof. David Schuyler, April 23, 2020)

- Regarding the possibility of coring studies to determine the trees’ exact ages: Some of the trees are simply too large to be cored. More than that, determining age through this method cannot be justified considering the harm to these very special trees that coring could possibly do.

- Star Trek’s George Hosato Takei, being of a much later generation, was actually named after King George VI of England.

References

- “Acts and Proceedings of the Eastern Synod of the Reformed Church in the United States, Shamokin, Pa., October 16, 1895.” Reformed Church Publication House, Philadelphia, 1895.

- Addendum, Lancaster New Era, May 26, 1959, p. 14.

- Asamen, Tim. “George – The Iconic Name”, in Discover Nikkei: Japanese Migrants and Their Descendants, April 20, 2016.

- Brubaker, Jack. “Largest Ginkgo in Pennsylvania No Stinko,” Intelligencer Journal/Lancaster New Era, May 10, 2013, p. 11.

- “Death of a Japanese Student,” Lancaster New Era, May 18, 1895, p. 8.

- “Death of a Japanese Student,” The Lancaster Inquirer, May 18, 1895, p. 1.

- “Death of Kinzo Kaneko, the Japanese,” The Frederick (Md.) News, May 18, 1895.

- “George Kinzo Kaneko Dead.” The Lancaster Examiner, May 18, 1895, p.5.

- Hino, Satoshi. Personal Communication, March 11, 2020.

- “Japanese Students Baptized.” Lancaster Intelligencer, April 8, 1885.

- “Memorial Trees in Bad Odor — To Be Cut,” Lancaster Sunday News, May 10, 1959.

- Miura, Ken-ichi. Head of Japanese Studies at F&M, Personal Communication, April 21, 2020.

- Nitobe, Inazo. “Bushido: The Soul of Japan.” CreateSpace Independent Publishing,

- 2017. (Originally published in 1900.)

- “Samurai,” Wikipedia (2020), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samurai.

- Schmidt, Rev. Ambrose M. “George Kinzo Kaneko,” (obituary), Franklin and Marshall

- College Record, ca 1895/1896.

- The Altoona Tribune, August 20, 1892.

- “The Kaneko Memorial,” The Everett (Pa.) Press, June 7, 1895, p. 3.

- “Tohoku Gakuin University and Franklin and Marshall College,” F&M Website (2020),

- https://www.fandm.edu/japanese