Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) is a much maligned, even demonized plant these days. It would probably win the Most Hated Tree Award hands down were votes to be taken.

Invasive, weedy, malodorous, allelopathic and otherwise detrimental to native species, of little economic value and, perhaps worst of all, preferred host of the dreaded Spotted Lantern Fly (Lycorma delicatula). These complaints are not without justification. But what is often lost in the rush to condemn and eradicate this species is any appreciation of the tree’s virtues which, it turns out, are considerable.

This article, by focusing on those virtues, seeks to provide more balance to our relation- ship with the Tree of Heaven.

Beauty

Heading this species’ inventory of virtues is, of course, its beauty. Ailanthus is an honored ornamental tree in China, and because of its exotic beauty was imported throughout much of the world during the 19th Century.

Hailed as an exquisite garden specimen, Tree of Heaven was first brought from China to Europe in the 1740’s, a time when chinoiserie (decorative arts reflecting Chinese motifs) was dominating European arts. It was imported to Philadelphia in 1784, to New York in 1820, and then brought to America a third time by Chinese immigrants who flocked to the West Coast during California’s Gold Rush years in the 1850s. (2,7) [Note 1]

Remarkably, Ailanthus comes in two attractive forms or varieties that differ in the color of their fruit (samaras). While not unique, this duality is relatively rare in plants outside of human-generated cultivars. The two forms are: (1) Ailanthus altissima forma altissima, which has greenish-yellow fruits; and (2) Ailanthus altissima forma erythrocarpa whose fruits are reddish-yellow. [Photographer Rosa Pomar captured both colors in a single close-up entitled “Beautiful Enemy.”]

In addition to these natural forms, a half dozen cultivars have been developed, though they are primarily found in China and rarely sold in America. Some of these cultivars are even more striking than the species, including (a) Purple Dragon, which has plum-colored leaves; (b) Pendulifolia whose long leaves drape elegantly from the tree’s limbs and branches; and (c) Erythrocarpa with fruits of brilliant red.

More spectacular still: On very rare occasions, Ailanthus sends up from its roots a mutated shoot that is largely, and stunningly, albino (10). Regarding a Rhode Island specimen, arborist Dustin Bowers explained (1):

A large Ailanthus altissima put out a mutated root sprout. It started out variegated and then went fully into albinism. When a plant sprout completely loses its chlorophyll, the only way it can keep living is if the large green main tree keeps supplying food to the small mutated sprout through the trunk or roots. That’s a rare find.

Rare freak mutations can happen at any time in a tree’s life. This one happened at a new bud that developed off the base of the tree; this obviously does not change the genetics of the whole tree, it only changed the genetics of any new cell growth from that new mutated sprout bud upward (any new cell growth above that bud). Sometimes chemical sprays can cause a mutation. Someone may have sprayed the trunk base which caused the dividing cells of that one bud to copy information wrong, thus creating the rare albinism on any new growth off that one bud.

Finally, discussion of the beauty associated with Tree of Heaven would not be complete without mentioning a couple of striking insects that this tree supports. While actually native to South Florida where its host plant is the Paradise Tree (Simarouba glauca), the Ailanthus Webworm (Atteva aurea) is a pretty little insect who has adapted to Ailanthus so thoroughly that its new host has influenced the moth’s common name.

Even more alluring is the large (4.5-inch wingspan) and beautiful Ailanthus Silkmoth (Samia cynthia). This Asian species was introduced to America in a failed effort to support a silk industry based upon its cocoon. The host plant of this gem is, needless to say, Ailanthus. S. cynthia’s current distribution is spotty along the Atlantic coast from Connecticut to Georgia and west to northern Kentucky. [Note 2]

Usefulness of Wood

Ailanthus wood is widely criticized for being of little use but this is not true if the tree is harvested at the right age and the wood is treated in the right way.

The wood of mature Ailanthus trees, pale yellow to light brown, close-grained and satiny, can be used in cabinet work, musical instruments, wooden bowls and other kitchenware, including the kitchen steamers that are so important in Chinese cuisine (2,5,11). Ailanthus wood has a porous texture and good natural luster; is easy to work with, whether using hand or machine tools; and stains and finishes well. “As material for cabinetmakers,” American botanist Charles Sprague Sargent noted 130 years ago, “it has few superiors among woods grown in the temperate region.” (13) [Note 3]

For furniture and other uses of lumber, Ailanthus wood — if harvested at the proper age — “is heavy, strong, and neither shrinks nor warps during seasoning.” (13). Hu (1979) notes that while the fast-growing young Ailanthus produces inferior wood that is brittle, non-durable and easily split, the wood of older (but not too old) trees is “comparable to that of ash or chestnut, and is moderately heavy, rather durable, difficult to split, and has a beautiful luster.” (5)

Because the trees exhibit rapid growth for the first few years, the trunk at that time has uneven texture between the inner and outer wood, and this can cause the wood to twist or crack during drying. However, techniques have been developed for drying the wood so as to prevent this cracking and so allowing it to be commercially harvested. Although a living Ailanthus tends to be very flexible, the wood is quite hard once properly dried. Moreover it has good insect resistance.

Mature, seasoned Ailanthus is also a good source of firewood across much of its original range, being moderately hard, heavy and readily available. It has comparable heat-producing properties to Black Walnut and Birch, burning “steadily and slowly, giving a clear bright flame, leaving a good bed of coals, and finishing with a small amount of ash” (4). Other writers have concluded that Ailanthus firewood is “better than Poplar and far better than Aspen, but not as good as Oak, more or less along the lines of Cherry firewood.” The wood can also be used to make charcoal for culinary purposes.

Ailanthus makes pulpwood that is ideal for books, lithography “and other purposes that require softness and opacity.” (6). For this a tree should be harvested before it’s 30 years old because “as the plants grow to full size, they begin to deteriorate.” (5)

Honey

Few people know of the honey that Tree of Heaven’s nectar and pollen help bees produce. Ailanto Honey is rare and produced in small amounts because of people’s dislike of Ailanthus, yet it is a “delicious variety of honey with a sweet taste.” (9) Difficult to find in America, Ailanto is mostly produced locally in Italy and Hungary.

Ailanto is initially amber-colored but crystalizes soon after harvest, giving a lighter, opaque pigment and a pleasant texture. Although the honey initially carries an unpleasant scent inherited from the tree, over time this disappears and the honey becomes “quite savory and fine-tasting.” (5,9) Indeed, its taste harmonizes nicely with other flavors such as fruits and cheeses.

Since the widespread Ailanthus blooms at the same time as other better known honey trees like Linden, Chestnut and Acacia, its nectar often blends with that of these other species.

Silk

Various countries of contemporary Europe have tried raising silkworms on Tree of Hea- ven. In China too the caterpillar of the Cynthia moth has been used with Ailanthus to produce a low-grade silk. An attempt was made in the late 1800s to introduce this in- dustry, along with the caterpillar and its tree, to the United States. The industry did not succeed although the Cynthia moth is now established in New York City and other parts of the Northeast, a region which has no shortage of host trees. [Note 4]

The moth’s silk is extremely durable but cannot easily be reeled off the cocoon and is thus spun like cotton or wool. S. cynthia is far less commonly used for silk than the domesticated Mulberry Silkmoth (Bombyx mori). Historically, as noted by Hu (1979),

the people of Shantung have demonstrated that Ailanthus can be a source for the silk industry. Although the area of production of Shantung silk or pongee and the number of people involved in the industry are relatively limited, the product has a worldwide reputation. Before World War II, Shantung silk was available in large cities in Asia, America and Europe. In Boston, members of the older generation praise it as a material for clothes and curtains. (5) [Note 5]

Medicine

Hu (1979) summed up the potential of Ailanthus for human health as such:

In traditional Chinese medicine, Ailanthus roots and leaves are used as antipsychotic agents and in the treatment of dysentery and intestinal bleeding. Ailanthus bark and fruits meanwhile are used for anti-hemorrhagic, antibacterials, anti-parasitic, and anti-inflammatory purposes. Unlike ginseng and other Chinese herbal medicines which are used for keeping the body healthy, Ailanthus leaves, roots, fruits and bark are used for curative purposes.

In comparison with other agents, the advantage of Ailanthus is that the supplies can be obtained readily in large quantity, and at reasonable price. There seems to be an open field for investigation in this area. (5)

While not a lot of scientific investigation has been conducted in the 40 years since Hu’s comments, more and more information is slowly becoming available. According to MedicineNet (15),

The dried bark from the trunk and root of Tree of Heaven are used for medicine. Until recently, Tree of Heaven was used only in folk medicine. But now, it is being investigated as a potential drug.

Tree of Heaven is used for diarrhea, asthma, cramps, epilepsy, fast heart rate, gonorrhea, malaria, and tapeworms. It has also been used as a bitter and a tonic. Some women use Tree of Heaven for vaginal infections and menstrual pain. In foods, the young leaves of the tree are eaten. In manufacturing, Tree of Heaven is used as insecticide.

MedicineNet notes, however, that adequate information on efficacy, dosing and side effects remains insufficient.

Lastly, Ailanto Honey is thought to have antibacterial, antioxidant, soothing and herbal tonic properties. In its raw form Ailanto seems useful for treating coughs, sore throats and upset stomach, and for providing like all honies numerous vitamins and minerals. (9)

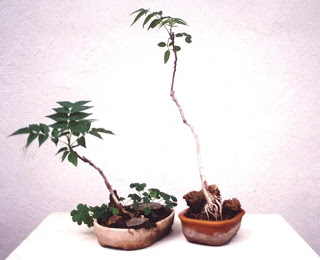

Bonsai

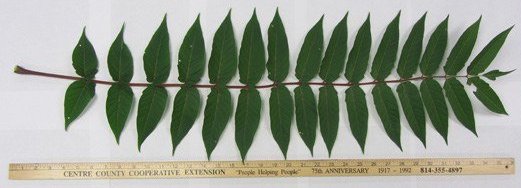

Tree of Heaven is seldom used in bonsai because it is such a fast grower (slow growers are easier to work with), its compound leaves are normally very large (small leaves are more esthetically proportional in bonsai), it has a relatively short lifespan (50 years is typical), and finally it exudes an odor that is, shall we say, unappealing.

It’s also true, however, that a large number of marginally bonsai-able trees are not used simply because they haven’t been sufficiently experimented with. Some bonsai en- thusiasts enjoy the challenge of the unusual, and still others relish violating bonsai ortho- doxy, and these hobbyists do sometimes work with this species. Blogger Josh Green has even coined the clever term Bonsailanthus for his potted specimen! (3)

When a free-growing Ailanthus has been repeatedly chopped near its base, the plant sometimes can develop an interesting trunk and root structure that, upon potting, is suitable to bonsai tastes. As for the large compound leaves: If the potted tree is defoli- ated, it will in most cases refoliate with “reduced” leaves.

One can purchase Ailanthus seeds from Amazon.com for the advertised purpose of creating “fast bonsai.” And the photo above shows potted Tree of Heaven being offered for sale as “hardy, fast bonsai.”

Energy and Air Renewal

As noted by Hu (1979), Tree of Heaven’s “luxuriant, feathered foliage proves an effective agent for capturing the radiant energy of the sun and transforming it into chemical energy in cellulose and other organic compounds.” (5) Open-grown Trees-of-Heaven are highly efficient at photosynthesis and store large quantities of photosynthate in stems and roots (2).

In addition, the efficiency of its leaves is complemented by Ailanthus’ capacity for fast growth which furnishes space for storing photosynthesized energy. “Young plants grow unusually fast in height,” Hu points out, “and older ones increase noticeably in girth. Thus the trunk and large branches are excellent organs for the storage of the chemical energy” which can later be released as firewood or charcoal. (5)

Hu further notes that Ailanthus, with its large compound leaves, provides the largest possible surface for effective photosynthesis and its oxygen byproduct, which is then released into the atmosphere. The per minute consumption of oxygen by cars and airplanes is hundreds to thousands of times more than such consumption by people, Hu said. And since trees are the most effective green plants for air renewal, “wise use of Ailanthus should be promoted.”

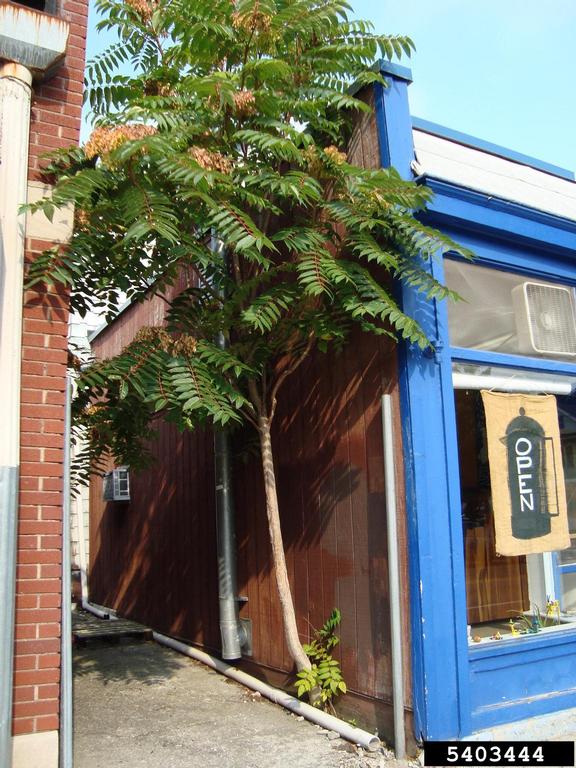

Survivability

With paper-thin bark and relatively thin trunks and branching, Ailanthus can give an impression of fragility. Nothing could be more misleading, for this species prevails against a host of environmental stressors that would doom most other trees. In fact, probably no tree in America is built for survival any better than Tree of Heaven. As one scientist has begrudgingly admitted, “As an ecologist, I detest this tree but I also admire its ability to survive in the most harsh situations.”

The environmental challenges that Ailanthus can overcome comprise a lengthy list. For example, the species is tolerant of most industrial pollutants (a notable exception being ozone pollution). In one study, Ailanthus showed the least damage and the best growth of 8 urban tree species confronted by pollution. (2)

Nor is the underlying substrate very important for successful germination of Ailanthus seeds. Unlike many other trees, Ailanthus seeds can germinate and establish a foothold in highly compacted soil, in pavement cracks, and in sites contaminated by roadside salt. (2)

Tree of Heaven, then, is renown for its ability to tolerate the smoke, dust and pollution of America’s eastern cities. Compacted soil, paved-over soil, and intentional or accidental injury to its trunk…all are solvable problems for Ailanthus. This species, after all, provides the central metaphor for Betty Smith’s famous 1943 novel, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Here, the tree’s persistent ability to flourish in an impoverished inner city environment mirrored Smith’s desire as a little girl to better herself. (14)

Another major stressor is drought. Aided by its large, water-storing roots, Tree of Heaven can tolerate dry, rocky soil that is wracked by drought for several months. During the Kansas’ Dust Bowl Drought of 1934, in fact, the top tree survivors were Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) and — you guessed it — Ailanthus (2). Even Ailanthus seedlings show remarkable drought tolerance. [Note 6]

Tree of Heaven has a pretty effective strategy for dealing with brush fire. Soon after a tree has been top-killed by fire, sprouts emerge from its roots, root crown, and bole (such vegetative regeneration occurs after any other above-ground damage as well, such as mechanical brush-clearing or severe browsing by deer.) Tree of Heaven can also re-establish from seed after fire. (2)

In the past, Ailanthus has been used to rehabilitate mine spoils in the eastern United States. Being tolerant of saline soils and low pH, Tree of Heaven shows better growth on mine spoils than most native species. Due to its tendency to spread on disturbed sites, however, it generally is no longer used for site rehabilitation (2).

Tree of Heaven is the only member of the Ailanthus genus that can survive temperate temperatures; all other Ailanthus species are strictly tropical. A. altissima survives temperatures as low as -38 F and as high as 110 F, a most impressive range.

Tolerance of environmental stressors is only half of Tree of Heaven’s arsenal for survival. Prodigious reproduction and growth are its other weapons. A single female can produce 300,000 seeds per year, most of which are viable (7). In one study, Ailanthus had the greatest seed production of 10 overstory trees, and its seed production was 40 times that of its closest rival. Moreover, Ailanthus can continue producing boatloads of seeds well into old age, such that a single female can potentially produce 52 million offspring during her lifetime. (8) This number, for a single tree, is difficult to comprehend.

But seeding is not even the most potent way that Tree of Heaven reproduces. Suckers can emerge from roots 50-90 feet from the parent tree (2,7) and will do so if the parent is injured. For example, while deer don’t generally favor Ailanthus, they sometimes do eat young sprouts right back to the ground, after which the tree generates new leaves and stems in no time. Through sprouting, Ailanthus can not only produce monoculture stands over a fair swath of land, but it can also achieve a kind of immortality. While an individual tree of this short-lived species can at best barely surpass 100 years, successive genera- tions of sprouted clones —genetically identical to the parent tree — live on. In this way, the first tree brought to America in 1784 is in a sense still living in Philadelphia today, some 236 years later.

Finally, Ailanthus is among the fastest-growing trees in North America (2). Both the com- mon name (tree of heaven) and the scientific name (Ailanthus, meaning sky tree) refer to the species’ ability to attain height quickly. Seedlings can grow 3-6 feet in their 1st year and sprouts often grow even faster than seedlings. (2) Ailanthus, in fact, can grow taller three times faster than even Norway Maple (Acer platanoides), which itself is no slouch at survival skills.

Bottom Line

Tree of Heaven has much to offer the world if it is grown and utilized in disciplined ways. Selected specimens can be nurtured while undesired offspring are removed, much as is done in China. [Note 7] And if one must, mature Ailanthus can be treated against Spotted Lantern Fly (via injections, sticky tape, etc.) if one doesn’t mind killing non-target species as well.

Perhaps too, infertile and non-suckering cultivars will eventually be developed so that this magnificent tree can be enjoyed without the problems that its high reproductive potential currently cause.

Final words on Tree of Heaven are best spoken by Chinese botanist Shiu-Ying Hu:

Through wise use, Ailanthus can be a blessing to people, and by neglect it can be a curse. If the American people want to have the benefit of Ailanthus, they must be aware of its merits and short- comings. Disciplined, Ailanthus should be allowed to grow, for it has much to contribute to the American people. [Note 8]